The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein proposed a final solution for philosophy in his twenties, and then took up teaching and gardening until he realized that people were abusing his intellectual authority. Strangely, that authority arose from his insistence that much of what philosophers wrote shouldn’t be considered philosophy, because it was concerned with matters that could not be decided. Taking a less charitable perspective, Wittgenstein set himself up as arbiter of what was and was not philosophy, and his desperate peers submitted to the force of his intellect.

I wonder whether Wittgenstein recognized the similarities to the program undertaken by Socrates in ancient Athens. Socrates, assuming that he knew nothing, went about seeking wisdom. In questioning the ethical reasoning of his peers, he exposed the inconsistency of their precepts. Having clarified the relationships between theory and practice, Socrates (as represented by Plato) then proposed his own solutions to the ethical problems of the day.

To the outside observer, the similarity between Wittgenstein and Socrates might be cause for despair. After nearly three millennia, the same fundamental problem remains: no philosophy has stood the test of its application. Actually, that’s not entirely true: philosophy spins off independent disciplines, many of which are phenomenally successful. Philosophy is left with the hard questions, questions concerning ultimate truth and meaning that are difficult to pin down in a rapidly evolving culture. Where in tribal societies the concerns of the parent are inherited by the child, the information age has decoupled the generations. Thus every generation must invent anew – and necessarily either reformulate the truths of the past, or relearn them after decrying their irrelevance.

In general, we find two threads of philosophical practice in response to this dilemma: play the role of Socrates in every generation, or seek to narrow the scope of philosophy to matters susceptible to the fashionable tools of the day. Strangely, the histories of philosophy are dominated by the latter, though the arguments become more and more arcane in every generation. Each luminary writes principally in opposition to his or her immediate predecessors, and so can often be understood only in that context. This leads to some repetition in every third of fourth generation, as the reaction against the reaction re-iterates the original thinker, although the increasingly obscure terminology may hide that fact. Thus around 1800 we find Kant speaking of phenomena (our description of events) and noumena (the events in themselves), and concluding that while we cannot guarantee that the former reflects accurately the latter, our survival as a species implies that there must be some correspondence. Of course, this is just what Socrates offered 2600 years earlier in his parable of the cave.

Socrates proposed that universal education should be offered to ensure that citizens possessed the skills to maximize the correspondence between experience and description. Following Kant, it was the psychologists and neurophysiologists that took up the problem, seeking to illuminate the physiology that links experience to thoughts. The first flowering of that effort was in the work of Sigmund Freud. As presented in Ideas: Invention from Fire to Freud, the early psychoanalysts stood on the brink of building a complete theory of human culture, but Freud drew back when confronted with the non-local spiritual experience of women that reported being molested by men at a distance. Freud’s conclusion was that he was being manipulated by his patients, and he abandoned his inquiries.

One consistent thread in philosophy is fertilization by its progeny. The insights of physics, chemistry and biology illuminate and constrain the forms of experience, and so clarify the analysis of the philosopher. The progeny, however, also narrow the scope of their study to exclude that which cannot be explained. For this reason, I tend to trust the original thinkers – the ancient Greeks, Hindus and Chinese – who reported their experience without the filter of professional respectability. I assert that Freud was hamstrung by this prejudice. As regards the matter of spirituality, I’ll defer to the ancients.

This long introduction serves to motivate what follows: I believe that the program of the early philosophers had an element that was missing in latter generations. They recognized the potential of the intellect, and sought to strengthen it. They were not concerned narrowly with truth, which seduces with its promises of certain deduction. Instead, they sought to build power in humanity as a whole – perhaps simply so they could have more interesting conversations. Be that as it may, in reading the history of philosophy, I believe that much controversy can be settled by advancing a model of intellect, and recognizing that philosophers that spoke with greatest certainty were those predisposed to focus on specific aspects of the intellect, thereby simplifying what evidently is an intractably complex problem.

That they belittled their predecessors reflected the assumption that all minds operate alike, an error that our autistic brothers and sisters are now forcing us to confront. Taking individual variation in the intellect as a given, the history of philosophical study can be mined to reveal its full richness.

This post builds on the propositions originally formulated in Ideas, Ideally. It adds pretty pictures that will hopefully make the model of intellect more apprehensible.

The Role of Intellect

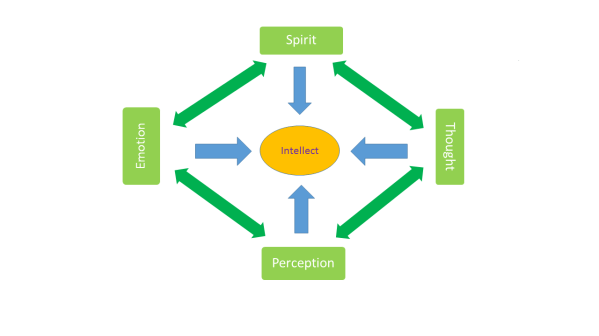

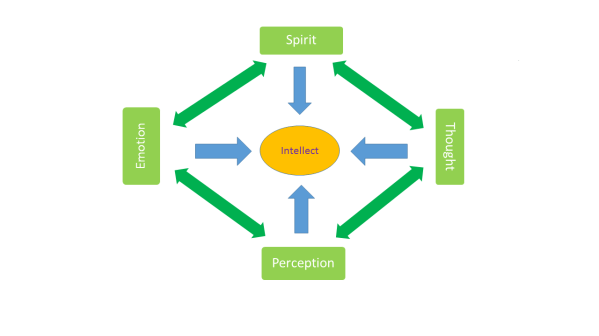

Recognizing that humanity’s evolutionary advantage is in the power of our minds, I have proposed to define intellect as the faculty that synthesizes our mental states. To understand the operation of intellect, we must first characterize our mental states, and then explore the possibilities for their synthesis.

Survival is a manifestation of successful relation to the world. When beginning to enumerate mental states, we benefit by considering the structure of those relationships. As concerns the mind, I recognize four immediate categories of relation, three of which are exhibited in equal degree by most animals. Of those first three, I differentiate sensory perception of our environment from the intimate physiological response of emotions. These two are most immediately concerned with our survival – the latter as the feedback signal that regulates our interaction with the world around us. The third category consists of spiritual influences that organize collective behaviors – such as the swarming attacks of bees – that may not serve the survival of the individual.

These three categories define the intellectual dynamic of Darwinian evolution, behaviors that we classify as instinctual. Even among creatures lacking a nervous system, intellect still operates, just through tissues and organs that are either less malleable or less effective at encoding information. In an herbivore, the emotion of hunger stimulates foraging, a complex interaction of muscles to navigate the sensed physical environment to locate food. Success is rewarded by satiation, and possibly sufficient surplus of energy to trigger the emotions that drive mating. As this simple illustration suggests, the intellect manifests as behaviors that couple sensation and emotion.

But the feedback is more widespread than the example suggests. Modern ecosystems are chemically determined by the existence of life: free oxygen, soil and the food chain are all side effects of biochemistry. The physical and chemical environment determines sensation. More subtly, the same holds true in the realm of spirit, which contains reservoirs of energy and intention that can become enmeshed in the external world, influencing the emotions of living things, and consequently their behaviors. Through that interaction, the spiritual reservoirs are themselves modified. In part, that reflects that physical commonality of spiritual interaction with metabolic activity (See That’s the Spirit). Spiritual forms can gain energy and spread influence through their interaction with matter, including biological forms. Finally, emotion drives the behavior of living creatures, determining how they modify their ecosystem. Successful individuals achieve dominance in part by attracting spiritual energies that force others to support their behavior.

But the feedback is more widespread than the example suggests. Modern ecosystems are chemically determined by the existence of life: free oxygen, soil and the food chain are all side effects of biochemistry. The physical and chemical environment determines sensation. More subtly, the same holds true in the realm of spirit, which contains reservoirs of energy and intention that can become enmeshed in the external world, influencing the emotions of living things, and consequently their behaviors. Through that interaction, the spiritual reservoirs are themselves modified. In part, that reflects that physical commonality of spiritual interaction with metabolic activity (See That’s the Spirit). Spiritual forms can gain energy and spread influence through their interaction with matter, including biological forms. Finally, emotion drives the behavior of living creatures, determining how they modify their ecosystem. Successful individuals achieve dominance in part by attracting spiritual energies that force others to support their behavior.

Recognizing the significance of the interaction between biological and spiritual forms, I find it useful to think of life as their co-evolution. Without that coupling, geology and chemistry would hold sway over the earth without any meaningful purpose.

O, Humanity!

Multicellular organisms dominate their ecosystem by optimizing the chemical environment of cells specialized to perform specific functions. Most obvious in many cases is the differentiation between the protective dermis and the organs of digestion that produce refined foodstuff for the dermis. In the case of the higher animals, of course, the specialization and organization of cells is wondrous. The layers of skin, the placement and density of follicles and sensory bulbs of nerves: these boggle our comprehension.

The evolution of multicellular organisms reflects two requirements: distribution and coordination. The first is obviously seen in the circulatory systems that distribute gases and fluids, but it is also manifested in the skeletal system that translates muscle contractions into motion. Coordination is also implemented through the circulatory system via the release of hormones that affect the organism as a whole. The nervous system is far more refined in its targeting, using the transmission of electrical signals to coordinate the behavior of specific tissues.

While the history of cellular innovation may never be known, the miracle of thought became inevitable when nerves evolved structures that chained the transmission of electrical signals along networks of nerves. This meant that the instinctual behaviors once triggered by sensation and spirit could be induced without the original stimulus by the firing of a nerve. This is accomplished most efficiently by the clustering of nerves in nodes, the most significant being the brain. In the higher animals, the progressive reallocation of metabolic resources to the brain is evidence of the benefits of signal processing by networks of nerves.

In the early stages, the signal processing provided by the brain stem was focused primarily on individual survival and procreation. Even today, reptiles are rarely social creatures. In birds and mammals, the limbic system manages social behaviors, while the cortex supports higher forms of thought.

So what is thought? In On Intellect, Jeff Hawkins of the Redwood Neuroscience Institute summarized the science that demonstrates that the cortex is a structure that categorizes experience to coordinate behavior. While initially that categorization would have been focused on the first three categories of intellectual stimulus, by the mechanism of network stimulation, eventually the internal operation of the network would have become an independent source of intellectual stimulus. Thus arose thought: the stimulation of the intellect by the brain.

So what is thought? In On Intellect, Jeff Hawkins of the Redwood Neuroscience Institute summarized the science that demonstrates that the cortex is a structure that categorizes experience to coordinate behavior. While initially that categorization would have been focused on the first three categories of intellectual stimulus, by the mechanism of network stimulation, eventually the internal operation of the network would have become an independent source of intellectual stimulus. Thus arose thought: the stimulation of the intellect by the brain.

Obviously thought has an ancient lineage, dating back even to insects. But full expression of its potentiality required coupling of that capacity to skills that could be used to reorganize the environment and thus control sensation. Birds and octopi manifest that to a limited extent, but primates to a degree that flowered to environmental dominance with the arrival of homo sapiens sapiens. We create tools that allow us to enhance our biology in real time, where every prior creature was allowed that opportunity – and then only imprecisely – through procreation.

While today we tend to emphasize the power of our material tools, the brain also allows a far more precise interaction with the spiritual realm. I understand that souls are composed of electrical charge decoupled from mass. Nerves channel and interpret the flow of electrical charge. As regards the emotions, nerves also affect our endocrine glands, muscles, organs and metabolism. Thus the brain provides methods for coupling thought to spirit and emotion, methods that are far more powerful than the couplings previously available to intellect.

As the influence of spirit is most evident in social activity, we should note the importance of language in facilitating the coupling of spirit to thought. While all mental states are abstractions of the underlying reality, words alone are capable of conveying our apprehension of that reality to another. Modern cultures are rooted in the conventions adopted for the association of words with experience. The ability of communities to coordinate effort to solve problems depends on the consistency and integrity of their use. Communities that honor clarity and honesty evolve social structures that may manifest as completely new forms of spirit. The ancients recognized these as “gods.”

Love of Wisdom

I have proposed to characterize Philosophy – the “love of wisdom” sought by the ancient Greeks – as study of the operation of the intellect. Here I understand intellect not narrowly as a manifestation of reason, but broadly as any process that couples the behavior of a living organism to the world around it. Intellect, in this view, mediates the interplay of the elements of reality through living creatures. Bringing together in humanity the dexterity and strength to create tools with the capacity of thought, nature manifested the potential to outgrow Darwin’s evolution through natural selection. Philosophers seek to organize that effort.

If that effort occurred in a vacuum, we might better be able to measure our progress. But it does not. Humanity is the culmination of a billion years over which life insinuated itself into the material substrate of the earth. That integration involves enormous amounts of energy, and disruption of the natural order threatens all of the higher lifeforms with extinction. The complexity of ecosystems makes it almost impossible to predict accurately the consequences of human intervention, and our facility with tools means that often we are the last creatures to feel the full force of disruption. Whether through clear-cutting of forests, the suffocation of once-fertile soils with covers of asphalt and concrete or the ubiquity of air conditioning, in fact our disruption of ecosystems often produces immediate advantage for us.

Our indulgence of those opportunities is a sign of dangerous immaturity. That immaturity is most dangerous in two scenarios. The first is when our primitive animal instincts infect our thinking, causing us to engage in contests for dominance using the most sophisticated tools that we can create. During the Cold War, the world as a whole was threatened by the nuclear arms race. While most nations appear to have recognized the insanity of direct military conflict, many nations still seek to define spheres of cultural hegemony through practices that require profligate consumption of fossil fuels. Unless reversed, that consumption will see human civilization destroyed by global warming. This second threat – the danger of inattention – manifests over many generations, and while no less deadly is far harder to address, not least because in the short term many beneficial outcomes accrue to the exploiting communities.

Under such circumstances, most parents deny children access to firearms and matches. And so it is with our spiritual predecessors. As they began to understand our potential by exploration of our minds, they have been forced to resist our head-long rush to Darwinian dominance.

If this sounds incredibly complex and ambiguous, it is. Most of the early philosophers counseled their peers to reticence. They sought to create a safe preserve for the operation of thought. Over time, that manifested through the formation of ideas that stood as bastions against disruption of human intellect by base motivations.

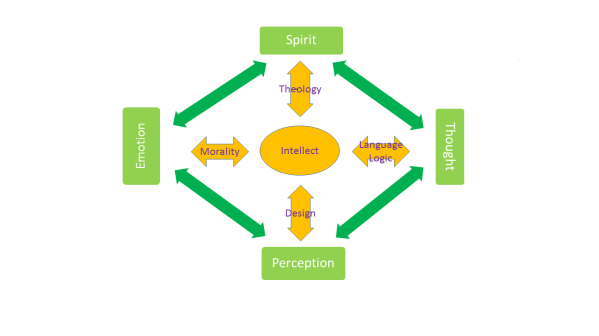

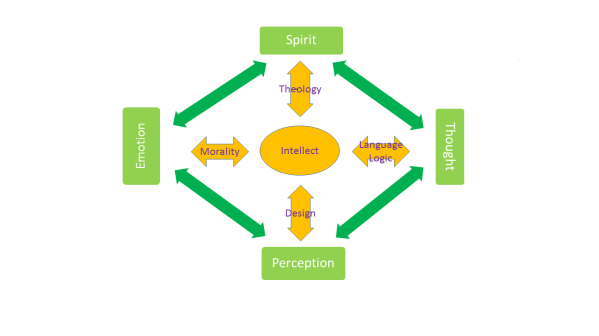

The principal threads of philosophical discourse can be understood as filters through which the human intellect manages its interaction with the sources of our mental states. At the interface to the physical world, we have the discipline of design that encompasses art as well as science and engineering. Design is concerned not only with the limits of practical possibility, but with ensuring that the environment that we create accommodates our emotional needs. Ethics attempts to organize and discipline our emotional experience, building reserves of good will that facilitate collaboration. Language and logic tame the profligate domain of thought, which if left unchecked devolves into incoherence or insanity. And at the interface between intellect and spirit, we have the bastion of theology that ensures that our faith is invested with personalities that respect our potential and seek to facilitate its flowering into mature judgment.

The principal threads of philosophical discourse can be understood as filters through which the human intellect manages its interaction with the sources of our mental states. At the interface to the physical world, we have the discipline of design that encompasses art as well as science and engineering. Design is concerned not only with the limits of practical possibility, but with ensuring that the environment that we create accommodates our emotional needs. Ethics attempts to organize and discipline our emotional experience, building reserves of good will that facilitate collaboration. Language and logic tame the profligate domain of thought, which if left unchecked devolves into incoherence or insanity. And at the interface between intellect and spirit, we have the bastion of theology that ensures that our faith is invested with personalities that respect our potential and seek to facilitate its flowering into mature judgment.

The history of philosophy demonstrates the difficulty of expanding the scope of human intellect. In the early days of Christianity, theology was considered dominant, but today design seems to be the most powerful method for bringing reality under human control. The unbridgeable gulf between physical reality as interpreted by our senses and the abstract realm of thought has long frustrated philosophers, and Aristotle’s dominance of intellectual discourse for 2000 years reflected in large part his belief that careful observation and logic could narrow that gap. Unfortunately, the strides made by technological innovation have allowed the spread of narcissism that undermines the work done by political theorists most concerned with the balance between morality and theology (nations being gods of a sort). Perhaps recognizing the futility of imposing purpose in the world, Post-Modernism celebrates the interplay of thoughts without reference to other experience.

And so it has been in age after age: profound thinkers set off to expand the scope of human intellect by focusing narrowly on opportunities in one discipline or another, only to have their successors shout “But you forgot about this!” In making clear the complexity of the philosophical quest, I hope that I will encourage future generations to humility, and the realization that no single mind can hold all the answers. Rather, not just the richness of human experience but our very survival is dependent upon the degree to which we allow our intellect to be disciplined by compassion in our hearts.

The Philosophical State

In parting, I offer these conclusions regarding my sense of where we should focus in the next era of philosophical discourse.

Concerning design: While nature holds its secrets, the Promethean fecundity of creative intelligence allows us to explore configurations of matter that could never be attained through other means. The sublime divinity of that capability must be yoked to compassionate service to life.

Concerning language and logic: No intellectual activity is sustainable unless we seek to honestly, clearly and precisely express our experience and expectations of this reality. In debate, we must avoid egotism that prompts us to consider our perspective to be superior to the perspective of other living things.

Concerning ethics: Morality is found in any system of values that expands the domain in which love is expressed.

Concerning theology: If love is a seeking after opportunities for the object of our affection to receive affirmation, then in its selflessness unconditional love is the only incorruptible unifying principle worthy of our faith.

Blessings and honor are due any that undertake to further the project of philosophy. I pray that some benefit may be found in the thoughts that I have here offered.

But the feedback is more widespread than the example suggests. Modern ecosystems are chemically determined by the existence of life: free oxygen, soil and the food chain are all side effects of biochemistry. The physical and chemical environment determines sensation. More subtly, the same holds true in the realm of spirit, which contains reservoirs of energy and intention that can become enmeshed in the external world, influencing the emotions of living things, and consequently their behaviors. Through that interaction, the spiritual reservoirs are themselves modified. In part, that reflects that physical commonality of spiritual interaction with metabolic activity (See

But the feedback is more widespread than the example suggests. Modern ecosystems are chemically determined by the existence of life: free oxygen, soil and the food chain are all side effects of biochemistry. The physical and chemical environment determines sensation. More subtly, the same holds true in the realm of spirit, which contains reservoirs of energy and intention that can become enmeshed in the external world, influencing the emotions of living things, and consequently their behaviors. Through that interaction, the spiritual reservoirs are themselves modified. In part, that reflects that physical commonality of spiritual interaction with metabolic activity (See  So what is thought? In On Intellect, Jeff Hawkins of the Redwood Neuroscience Institute summarized the science that demonstrates that the cortex is a structure that categorizes experience to coordinate behavior. While initially that categorization would have been focused on the first three categories of intellectual stimulus, by the mechanism of network stimulation, eventually the internal operation of the network would have become an independent source of intellectual stimulus. Thus arose thought: the stimulation of the intellect by the brain.

So what is thought? In On Intellect, Jeff Hawkins of the Redwood Neuroscience Institute summarized the science that demonstrates that the cortex is a structure that categorizes experience to coordinate behavior. While initially that categorization would have been focused on the first three categories of intellectual stimulus, by the mechanism of network stimulation, eventually the internal operation of the network would have become an independent source of intellectual stimulus. Thus arose thought: the stimulation of the intellect by the brain. The principal threads of philosophical discourse can be understood as filters through which the human intellect manages its interaction with the sources of our mental states. At the interface to the physical world, we have the discipline of design that encompasses art as well as science and engineering. Design is concerned not only with the limits of practical possibility, but with ensuring that the environment that we create accommodates our emotional needs. Ethics attempts to organize and discipline our emotional experience, building reserves of good will that facilitate collaboration. Language and logic tame the profligate domain of thought, which if left unchecked devolves into incoherence or insanity. And at the interface between intellect and spirit, we have the bastion of theology that ensures that our faith is invested with personalities that respect our potential and seek to facilitate its flowering into mature judgment.

The principal threads of philosophical discourse can be understood as filters through which the human intellect manages its interaction with the sources of our mental states. At the interface to the physical world, we have the discipline of design that encompasses art as well as science and engineering. Design is concerned not only with the limits of practical possibility, but with ensuring that the environment that we create accommodates our emotional needs. Ethics attempts to organize and discipline our emotional experience, building reserves of good will that facilitate collaboration. Language and logic tame the profligate domain of thought, which if left unchecked devolves into incoherence or insanity. And at the interface between intellect and spirit, we have the bastion of theology that ensures that our faith is invested with personalities that respect our potential and seek to facilitate its flowering into mature judgment.