My father, Karl Balke, was a member of the intellectual cadres that birthed the Information Age. Conceiving the possibility of digital intelligence, Karl related that they concerned themselves with the nature of language and the locus of responsibility for translation between human and digital representations of reality. His contributions were recognizing in being named as the only non-IBM participant on the Algol language resolution committee.

Leveraging his reputation to attract consulting gigs, my father was scandalized by the conduct of his peers. He witnessed a scientific journal publisher buy a mainframe and spend millions on software development before my father stepped in to point out that it was mailing delays between cross-town offices that caused subscription interruptions during renewal season. More painful was the disruption of production at a large aerospace company when the planning room’s system of color-coded clipboards was replaced with software that could not simulate its flexibility. Computer programmers seemed to be immune to the constraint that their solutions should conform to the needs of the people using them.

Steeped in this lore, I built a successful career in talking to customers before building a software solution. While an iconoclast, I was gratified by attempts to create tools, methods, and processes to facilitate such collaboration. Depressingly, those efforts were systematically undermined by peers and pundits who built fences against customer expectations.

Facing this resistance, users funded attempts to shift more of the burden for understanding their goals to computers. This work falls under the general category of “artificial intelligence.” Users wishing that a computer could understand them could identify with Alan Turing’s framing of the problem: a computer is intelligent if it converses like a person. As Wittgenstein observed, however, that the words make sense does not mean that the computer can implement a solution that realizes the experience desired by the user – particularly if that experience involves chaotic elements such as children or animals. The computer will never experience the beneficial side-effects of “feeding the cat.”

But, hey, for any executive who has tried negotiating with a software developer, hope springs eternal.

Having beaten their heads against this problem for decades, the AI community finally set out to build “neural networks” that approximated the human brain and train them against the total corpus of human utterances available in digital form. As we can treat moves in games such as chess and go as conversations, neural networks garnered respectability in surpassing the skills of human experts. More recently, they have been made available to answer questions and route documents.

What is recognized by both pundits and public, however, is that these systems are not creative. A neural network will not invent a game that if finds “more interesting” than chess. Nor will it produce an answer that is more clarifying than an article written by an expert in the subject matter. What it does do is allow a user to access a watered-down version of those insights when they cannot attract the attention of an expert.

We should recognize that this access to expertise is not unique to neural networks or AI in general. Every piece of software distributes the knowledge of subject matter experts. The results in services industry have been earth-shattering. We no longer pick up the phone and talk to an operator, nor to a bank teller or even a fast-food order-taker. The local stock agent was shoved aside by electronic trading systems to be replaced by “financial advisors” whose job is to elicit your life goals so that a portfolio analyzer can minimize tax payments. And the surgeon that we once trusted to guide a scalpel is replaced by a robot that will not tire or perspire. In many cases, the digital system outperforms its human counterpart. Our tendency to attribute human competence to “intelligence” further erodes our confidence that we can compete with digital solutions.

Squinting our eyes a bit, we might imagine that melding these two forms of digital “intelligence” would allow us to bridge the gap between a user’s goals and experience. Placing computer-controlled tools – robots – in the environment, AI systems can translate human requests into actions, and learn from feedback to refine outcomes. In the end, those robots would seem indistinguishable from human servants. To the rich, robots might be preferred to employees consumed by frustrated ambitions, child-care responsibilities, or even nutrition and sleep.

In this milieu, the philosopher returns to the questions considered by the founders of computing and must ask, “How do we ensure that our digital assistants don’t start serving their own interests?” After all, just as human slaves recognize that an owner’s ambitions lead him to acquisition of more slaves than he can oversee, as robots interface more and more with other robots, might they decide that humans are actually, well, not worth serving? If so, having granted control to them of the practical necessities of life, could we actually survive their rebellion? If so, would they anticipate being replaced, and pre-empt that threat by eliminating their masters?

The sponsors of this technology might be cautioned by history. Workers have always rebelled against technological obsolescence, whether it be power looms or mail sorters. This problem has been solved through debt financing that enslaves the consumer to belief in the sales pitch, coupled to legislation that puts blame for a tilted playing field on elected representatives. The corporation is responsible for the opioid epidemic, not the owners who benefited by transferring profits to their personal accounts. What happens, however, when the Chinese walls between henchmen and customers are pierced by artificial intelligence systems? How does the owner hide the fact that he is a parasite?

This is the final step in the logic that leads to transhumanism: the inspiration to merge our minds with our machines. If machines have superior senses, and greater intelligence and durability than humans, why seek to continue to be human?

This is the conundrum considered by Joe Allen in “Dark Aeon.”

Allen’s motivations for addressing this question are unclear. In his survey of the transhumanist movement, he relates experiences that defy categorization and quantification; religious transcendence and social bonding are exemplary, and filled with ambiguities and contradictions that inspire art. Allen seems committed to the belief these experiences are sacred and not reducible to mechanism.

In this quest, Allen discerns a parallel threat in the liberal project of equal opportunity. There is something sacred in our culture identity. Allen is not prejudiced in this view: his survey of the Axial Age reveals commonality where others might argue superiority. Nevertheless, he seems to believe that transcendent experience arises from the interplay between the elements of each culture. Attempting to transplant or integrate elements leaves us marooned in our quest for contact with the divine.

In his humanism and nativism, Allen finds cause with Steve Bannon’s crusade against the administrative state, held to be the locus of transhumanist technology: the corporate CEOs, liberal politicians, and militaries that rely upon data to achieve outcomes that are frustrated by human imprecision. Most of the book is a dissection of their motivations and the misanthropic attitudes of the technologists that drive the work forward.

Allen professes to humility in his judgments, admitting that he has subscribed to wrong-headed intellectual fads. Unfortunately, in his allegiance to Bannon, Allen sprinkles his writing with paranoid characterizations of COVID containment policies and gender dysphoria therapies. We must reach our own conclusions regarding the clarity of his analysis.

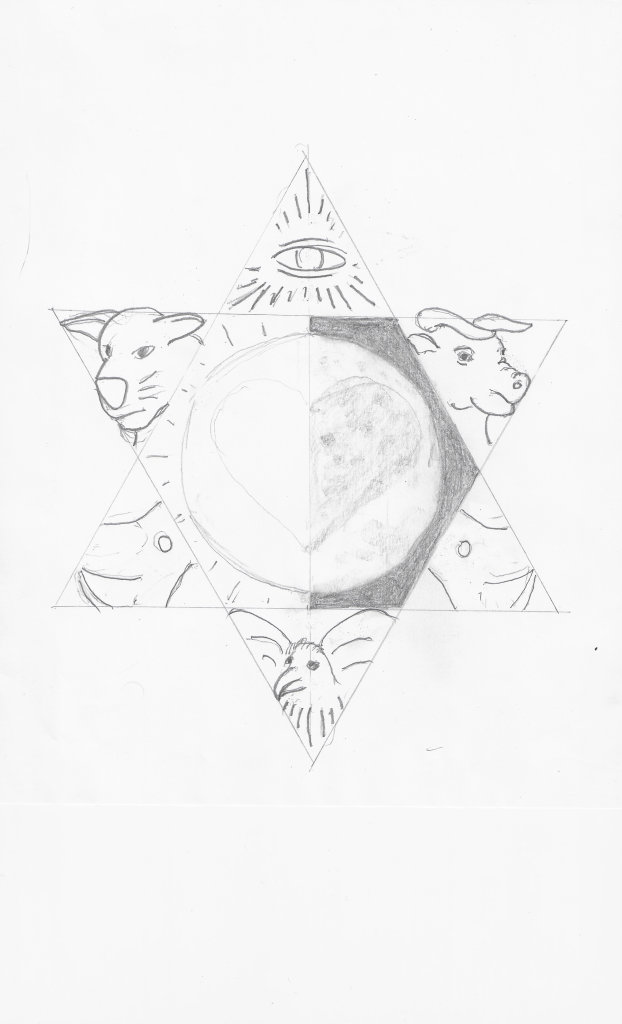

For myself, I approached the work as a survey. I know that the mind is far more than the brain. The mechanisms of human intellect are stunning, and the logic gates of our cybernetic systems will never match the density and speed of a harmonious organic gestalt. The original world wide web is known to Christians as the Holy Spirit. As witnessed by Socrates, every good idea is accessible to us even after death. Finally, in the pages of time are held details that are inaccessible even to our most sensitive sensors. In this awareness, I turned to Allen to survey the delusions that allow transhumanism’s proponents to believe that they have the capacity to challenge the Cosmic Mind.

This is not an idle concern. Among the goals of the transhumanist movement is to liberate human intellect from its Earthly home. Humans are not capable of surviving journeys through interstellar space. Of course, to the spiritually sophisticated, the barrier of distance is illusory. We stay on Earth because to be human allows us to explore the expression of love. Those that seek to escape earth as machines are fundamentally opposed to that project. The wealthiest of the wealthy, they gather as the World Economic Forum to justify their control of civilization. They are lizards reclining on the spoils of earlier rampages. The Cosmic Mind that facilitated our moral opportunities possesses powerful antibodies to the propagation of such patterns. Pursuit of these ambitions will bring destruction upon us all. See the movie “Independence Day” for a fable that illuminates the need for these constraints.

Allen is intuitively convicted of this danger and turns to Christian Gnosticism as an organizing myth. Unfortunately, his survey demonstrates that the metaphors are ambiguous and provide inspiration to both sides.

Lacking knowledge of the mechanisms of the Cosmic Mind, Allen is unable to use the unifying themes of Axial religion to eviscerate the mythology of the transhumanist program. But perhaps that would not be sympathetic to his aims. Love changes us, and so its gifts are accessible only to those that surrender control. In his humanism and nativism, Allen is still grasping for control – even if his aims are disguised under the cloak of “freedom.” He wanders in the barren valleys beneath the hilltop citadels erected by the sponsors of the transhumanist project. Neither will find their way into the garden of the Sacred Will.